About

RavenGuard is a 2D tactical RPG Roguelite experience that puts the player in charge of a small band of soldiers as they make their way though enemy lines in order to stop an evil tyrant. Starting with minimal resources, the player must scavenge up new tools and abilities in order to strengthen their army for the road ahead. With no guarantee what they player may find or have to fight, they must be quick to improvise and adapt, or suffer defeat. Between adventures out into the world, players are able to spend acquired gold to upgrade the skills they may come across, or unlock new leaders to lead their soldiers into battle.

As our team’s lead and sole designer, I was tasked with leading the charge on establishing our various system mechanics, level designs, game experience goals, and the overall balance of the game.

Development Info

– Project Type: Game

– Role: Lead Designer

– Tools Used: Unity, Aseprite, Google Sheets

– Team Size: 4-6

– Project Length: 9 Months

Game Info

– Genre: Roguelite/Tactical RPG

– Platform: PC

– Current Status:

Finished.

Personal Accomplishments

(Further details about these experiences and the project as a whole can be found below)

- Designed the HUD and menu UI

- Research Paper! Which can be read here!

- Inter-sub-team communication

- Arranged and managed multiple sessions of player play-testing.

- Art contributions (including 2D animation)

- 100+ skill designs (despite few making the final cut)

Pre-Production

Our goal for RavenGuard was to merge a Tactical RPG and a Roguelite. Based on this inspiration, our first design pillars were based on the differences usually found between the games in these genres:

1. Facing the unknown

2. Improvisation

3. Preparation

4. Puzzle Solving

Our early designs based on these pillars found issue after issue, often being unideal for both gameplay and production, even when looking ahead from such an early stage.

It occurred to me that a cause of this issue was the design pillars. They were designed based on differences, not the matching feelings both genres evoke. So, I redid the design pillars, instead focusing on the similarities, resulting in:

1. Player Growth / Empowerment over Time

2. Strategy and increasing options over Time

3. Control

4. Crisis Management

With these new core pillars, redoing our systems based around them provided more promising results.

RavenGuard would still come to have some systems that evoke feelings of improvisation or planning, but those feelings are secondary to creating the primary feelings. Designing systems to focus on the similarities helps to avoid the creation of over-complicated systems, and to create a more unified experience.

Reworking pillars of design might not always be the best idea, especially later in development, but being unwilling to even consider that they might need to be adjusted would have led the game down a very different path.

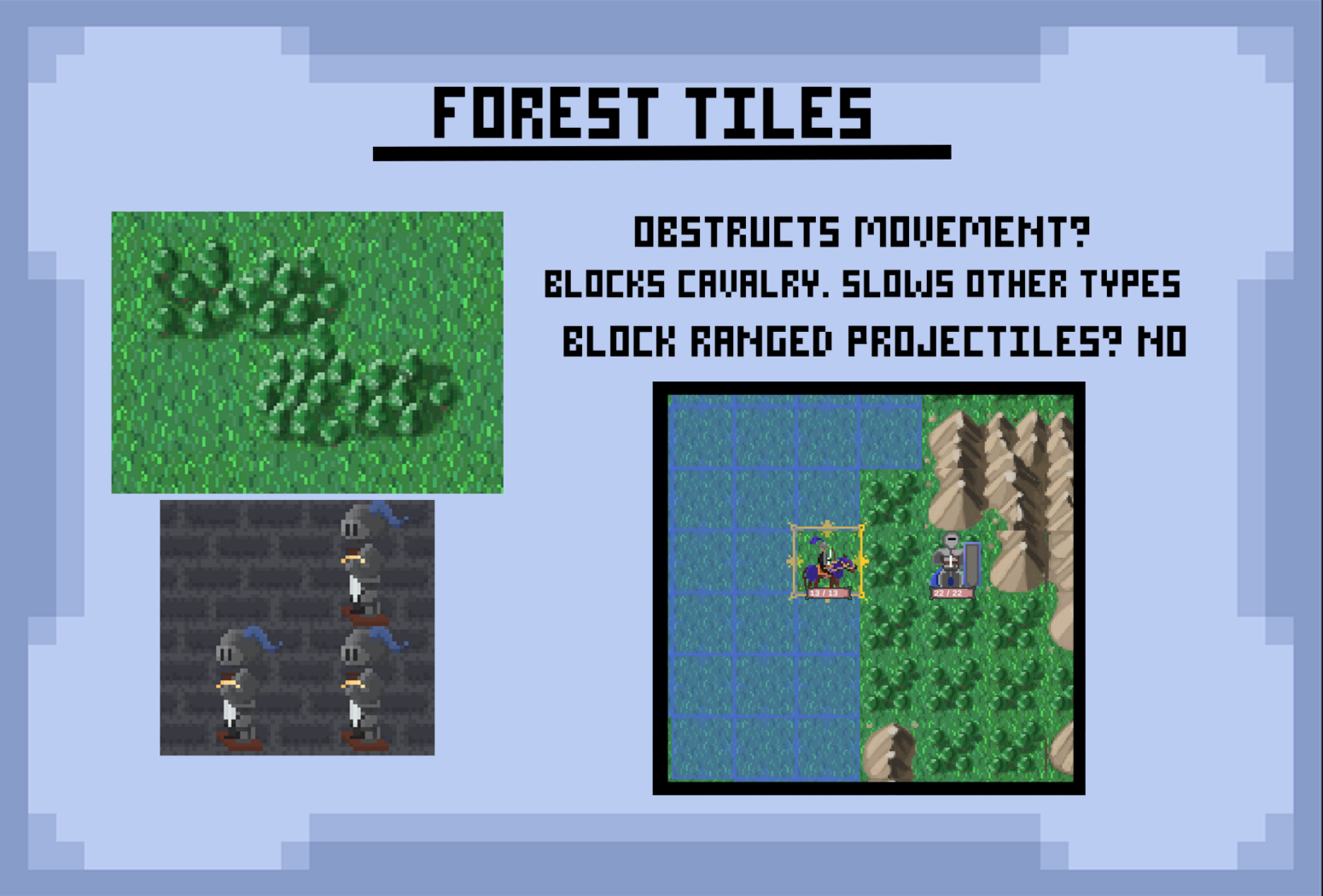

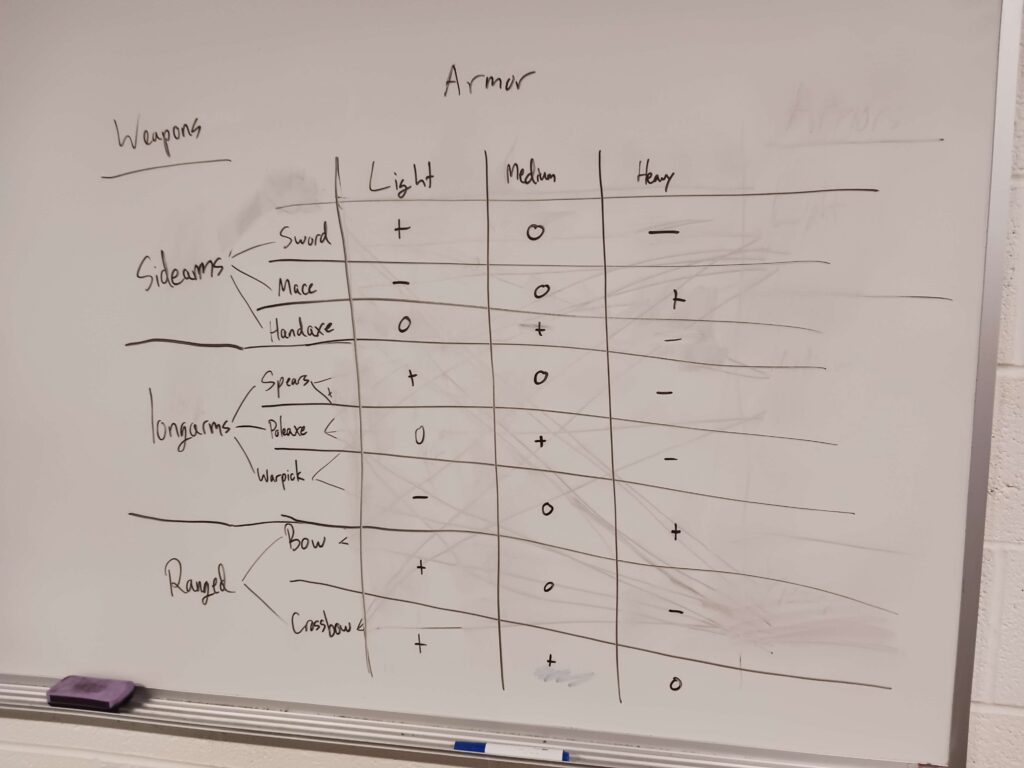

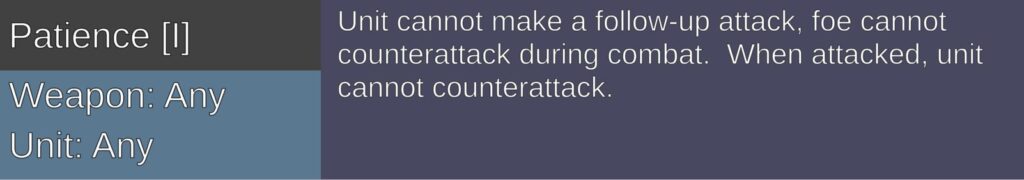

An early version of our weapon and armor interaction table which would eventually be extremely simplified.

System Design

Units

In RavenGuard, there are two greater classifications of units. Standard Units, and Paragon Units.

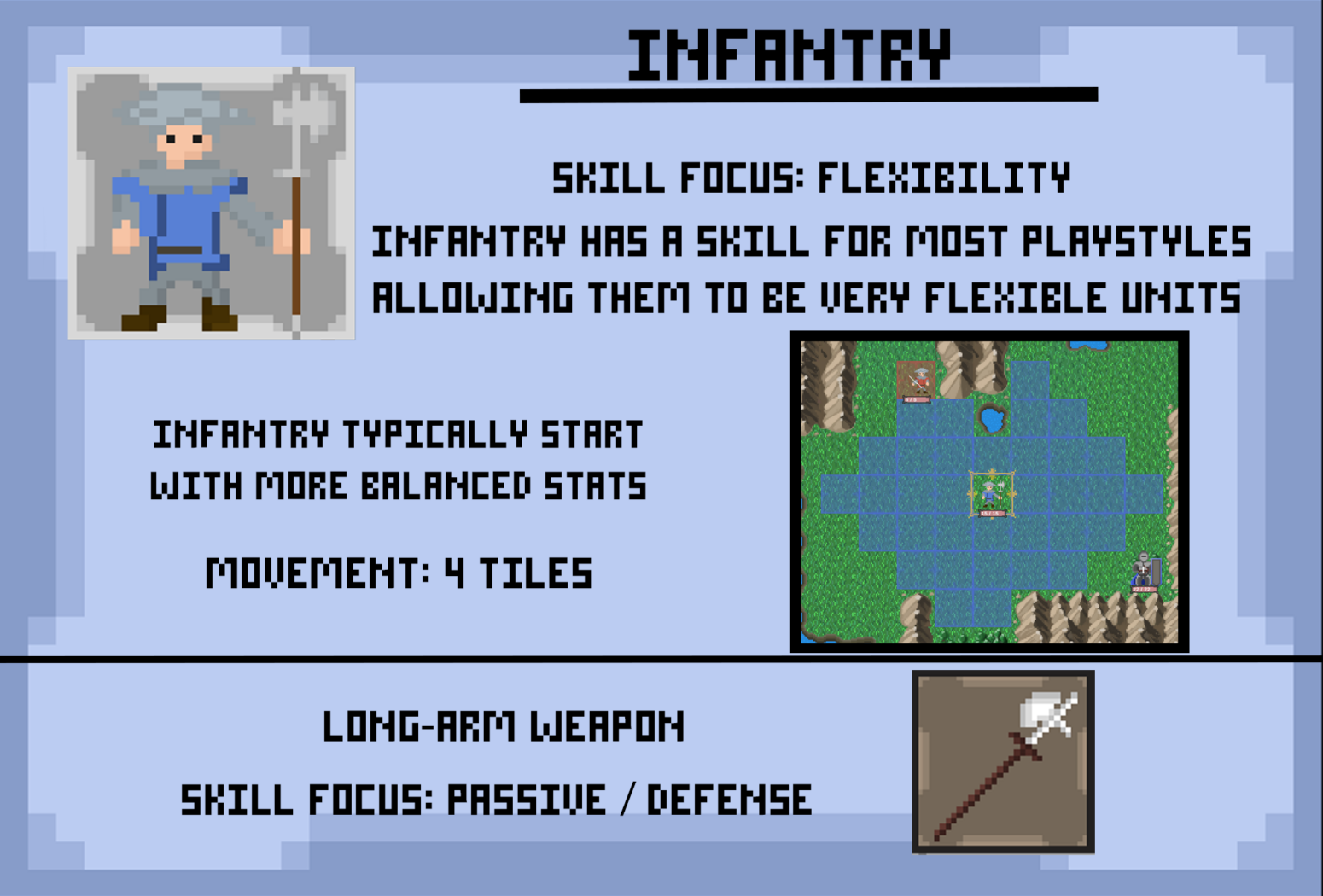

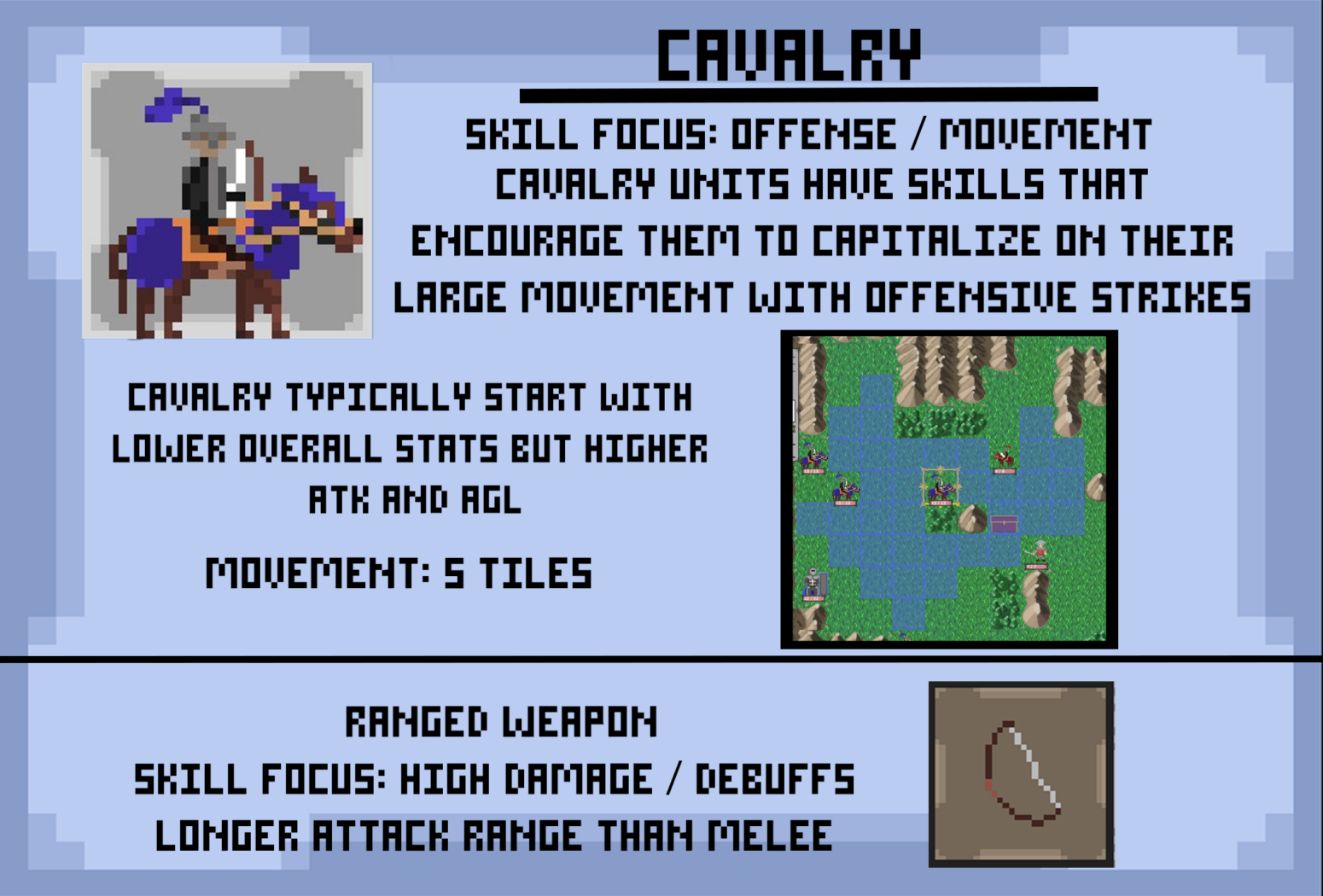

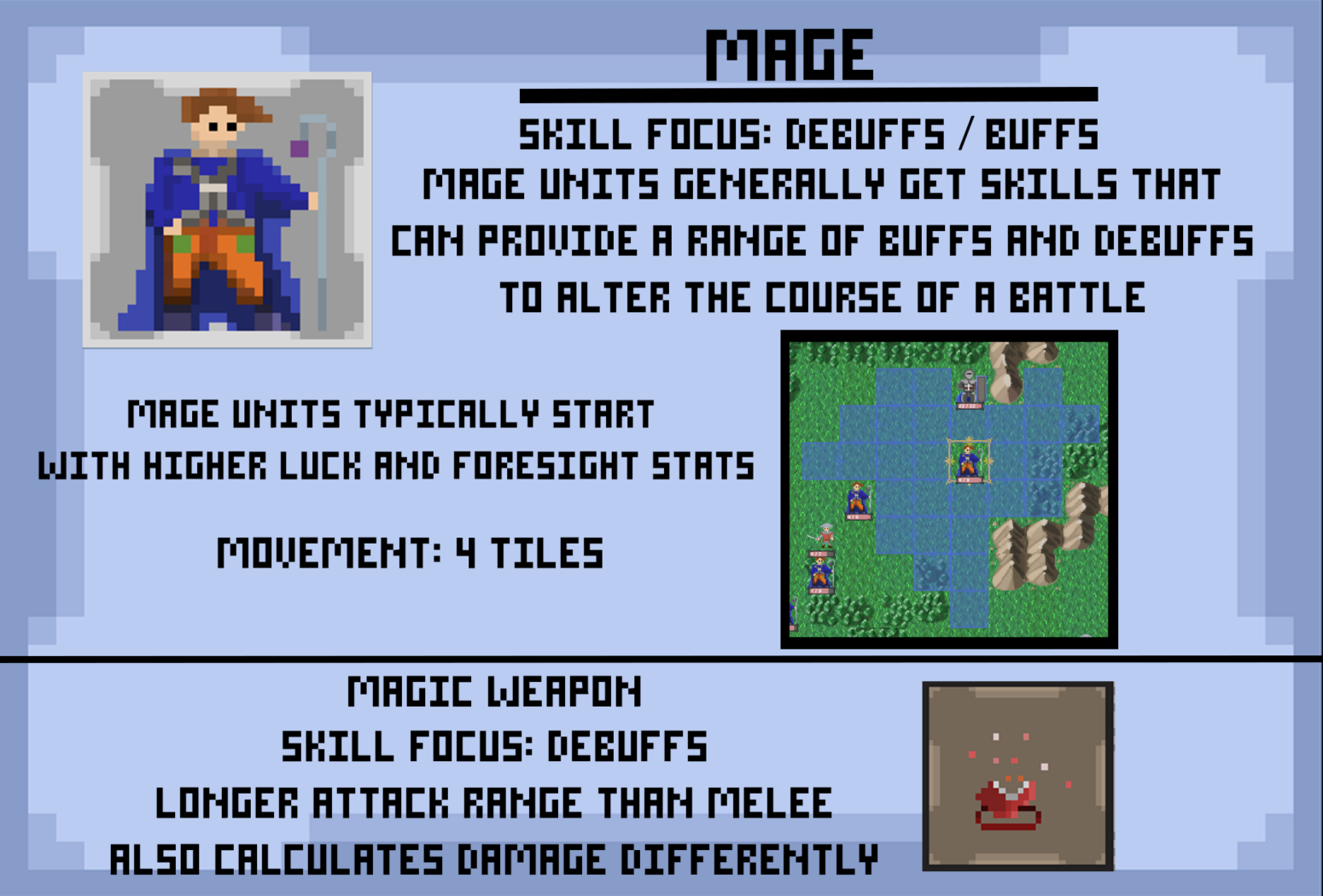

The majority are Standard Units. They have a class and a weapon. To the right, further details regarding these attributes can be found.

Before each run, players pick the Paragon they want to lead their army. Paragon units have two special functions, their Unique Ability, and unrestricted access to class specific skills.

A Paragon’s Unique Ability will affect the army as a whole, providing buffs and special abilities. As the player progresses through the game, these skills upgrade themselves in order to stay relevant and not fall by the wayside.

While they each still have a normal class akin to standard units, skills that are restricted based on class are all accessible to paragon units. So these units can be incredibly flexible, and allow for unique skill combinations.

Skills

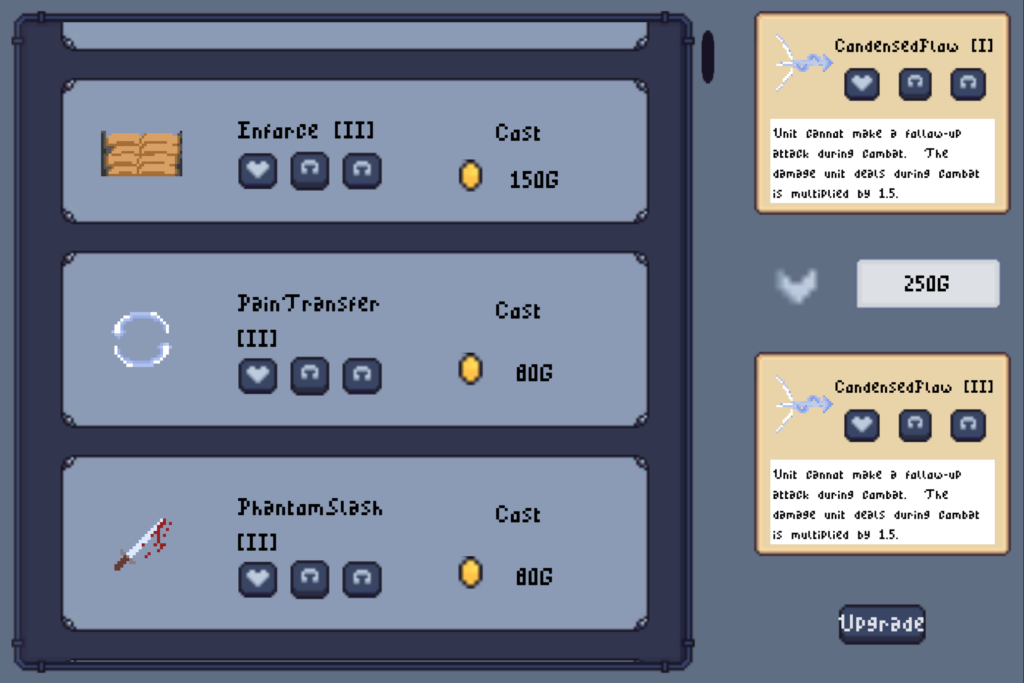

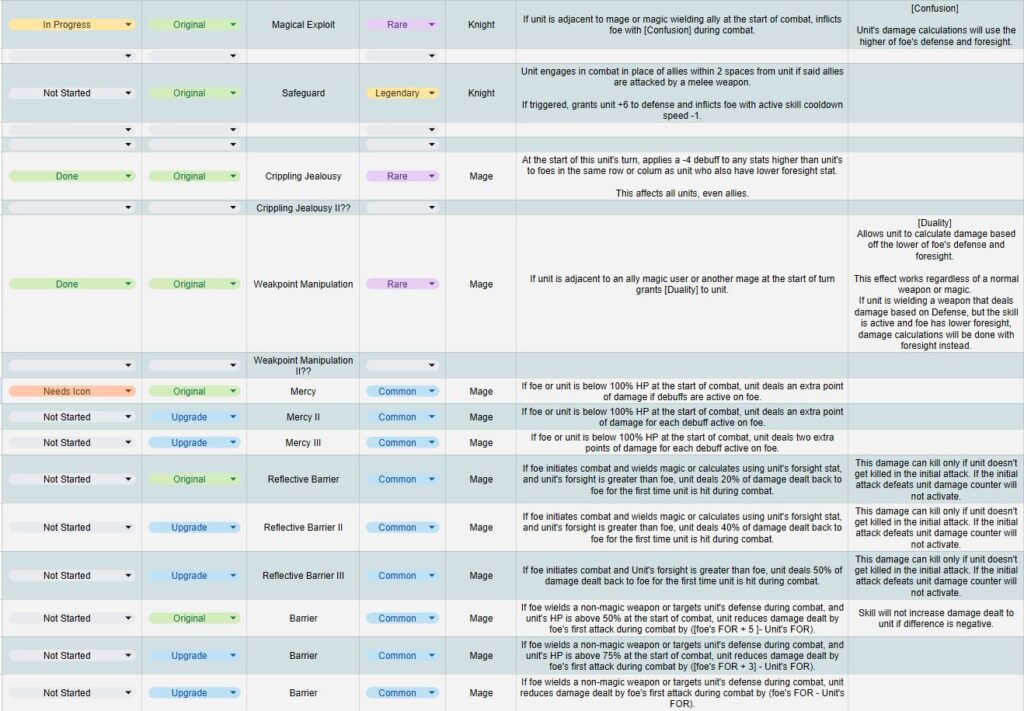

The bread and butter of player customization, skills are equip-able items players find that add extra functionality to units who equip them.

There are two types of skills, which I called Passive and Active.

Most skills are Passive. These skills each feature a condition that when met, grant the unit a bonus effect or increase in stats. These were created this way to encourage certain strategic play-styles, but also to allow players to shape their units to the style of tactics they wished to utilize.

Active skills instead provide an extra action for units to perform. Some of these have a cool-down, but unlike passive skills do not activate on their own. These were a way for players to get more options to choose during a run, expanding their options for movement or attacking.

Skill Design Evolution

Due to their prominence, skills were important for us to get right. The overall goal of the skill system was to offer players an intellectual challenge and a way to express their creativity and problem solving abilities. Skills were one of the earliest systems I began iterating on, first reaching the hands of players during our second project showcase.

Attempt #1

For this first batch of skills, the team decided to try and test more unique skills first, the ones that would really change the flow of the game. By the time of the showcase we had implemented 15 skills. After our testing these early skills, I noticed issues that came up with their designs.

1.) They rarely changed the outcome in combat

2.) Very few synergized well with each other

3.) Classes and weapons had no identity

The skills for this build ended up focusing on letting units fight in unorthodox ways at the cost of rarely altering stats. This not only made combat outcomes rarely change, but made what little build-crafting we had feel very uninteresting for the player.

Attempt #2

Combined with some scope adjustments we made that heavily simplified the game, I outlined guidelines for future skill development. I first created specific goals for where each weapon and unit should excel. I also decided on one major rule all passive skills would follow:

Every passive skill must have an activation condition or downsides.

This change turned the skills we had from being complete packages, to puzzle pieces who’s faults players would need to strategize around. The new skills created more decisions for the player to make, and more obstacles for them to overcome, resulting in a more engaging system, and one that was better aligned to RavenGuard’s experience goals.

Postmortem

Skill design was kept very open ended in the goal of making them feel unique and exciting to find. But this freedom made them significantly harder to create and implement. I believe placing some restrictions on what they could be from the beginning would have helped ease this burden.

Throughout most of RavenGuard’s production, I was our only designer, forcing me to split my focus between all our systems to make sure the designs were one step ahead of production. Typically my focus would be on one area for an extended time, before I put it aside until I needed to alter it.

This habit meant that our final skills came out in one, massive “batch”, so only the easier to make made the final cut. The more complicated ones came too late to properly plan for. Due to this, our final result was simply what we could make in time.

Making smaller batches of skills would have allowed them to be easier to create, implement, and test.

The item shop used by players to upgrade skills between runs

One of our first skills that ran into the issue of changing how combat played out without being able to change the overall result.

Level Design

Level Design

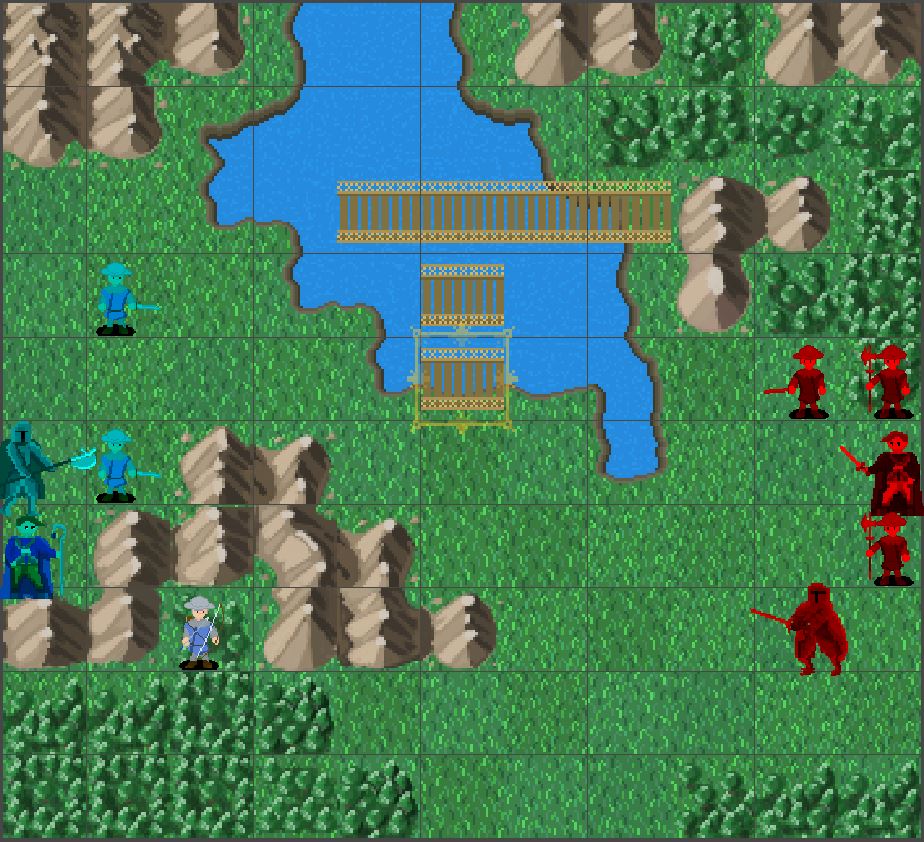

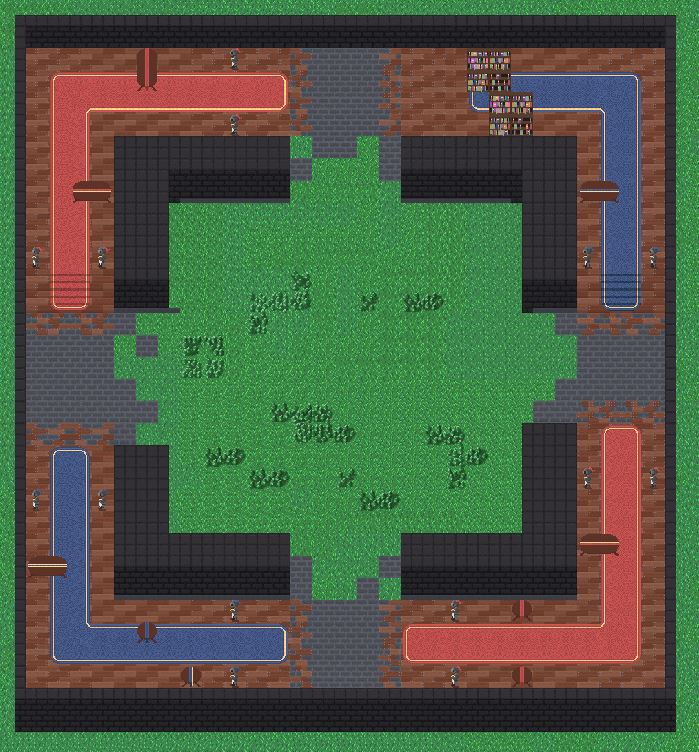

The way we made levels changed a lot over the course of production. Very early on, we wanted levels to be procedurally generated, to feel more like an open, explorable world then a selection of pre-made areas.

The early versions of our procedural generation involved an algorithm that would take premade separate pieces, and put them together. But while this system showed potential, it was too much effort to bring into a capable state with the time we had. So instead, we choose to hand make the levels.

The biggest advantage to this change was making it easier for us to create and adjust the levels based on player feedback. Another bonus we found was us being able to successfully create optional routing only accessible based on the player’s army composition. This was a feature we wanted, but couldn’t get with our procedural generation.

Iterating on our Level Design

After scrapping our plans for procedural generation, I produced a small batch of levels to playtest. These four levels varied a lot in size and detail. Players particularly enjoyed the exploration experience created by the largest level. This was a feeling I hadn’t considered previously, and decided for the next batch I’d try to accommodate it more.

But, the next batch of levels ended up creating too much room. They had players spending a lot of time moving their units between foes before anything happened, making these levels feel very tedious to play. They also failed to create any tactical decision making, as environmental pieces were too far apart to matter.

The very first change I tried was to downscale them. I figured the biggest, and easiest to fix issue was the levels’ size. For many of them, simply down-scaling them did help to reduce these issues. In other cases however, this was not enough. In these stages, it seemed to be that the stage was providing too much. So for these levels, I split them apart and designed new levels based on the pieces.

But come the final stages of the project, these new levels began to show faults. Players would get stuck early on, as the lack of skills and weaker units slowed the game down, making the large levels tougher and tedious to play.

I believe creating a variety of level sizes to scale alongside the player could have provided a smoother experience. Smaller levels worked better early in runs, allowing for faster progress, and larger levels worked better later when the players had more options. Unfortunately, this conclusion was made too late to be reflected for the most recent release of the game.

A before (left) and after (right) of one level that was shrunk in size.

Enemy Design

An important part of RavenGuard was what the players would be strategizing against. As our levels evolved, so did the requirements our enemies needed to fill.

Earlier in development when our levels were smaller, players and enemies had the same number of units, with very equal capabilities. This made fighting very costly for the player, with units often being defeated. With the larger levels, the number of enemies was increased to keep the stages from feeling empty. They were also reduced in individual strength to make up for the increase in number.

The biggest challenge was designing how our enemies would act. We had begun with them moving randomly, and targeting the player when they could, but it was far from creating the experience we desired.

After some brain storming, I helped us come to the conclusion of making a rating based decision tree AI for our foes. Essentially, the AI would pick an move it wished to perform, then rate all its options before picking the best one.

I aided in designing the rating system for the AI, to ensure it factored in the more important variables when making its decisions. The AI does not consider everything, but we intentionally handicapped it to make its development easier, and make it easier to fight.

This rating system ended up working out quite well. The new AI made making smart choices even more important for the player, as misplays would be noticed and punished. This helped to enhance the tactical side of the game, making it feel more decision oriented than coming down to brute strength.

During my tuning of the system, I realized that the AI began to feel too similar between units, often using a tank the same way it would use a ranged support. I put together plans for creating a “personality” system for the AI, would simply change the way certain factors are weighted depending on the unit. Ideally changing a unit’s behavior. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, this feature was not implemented.

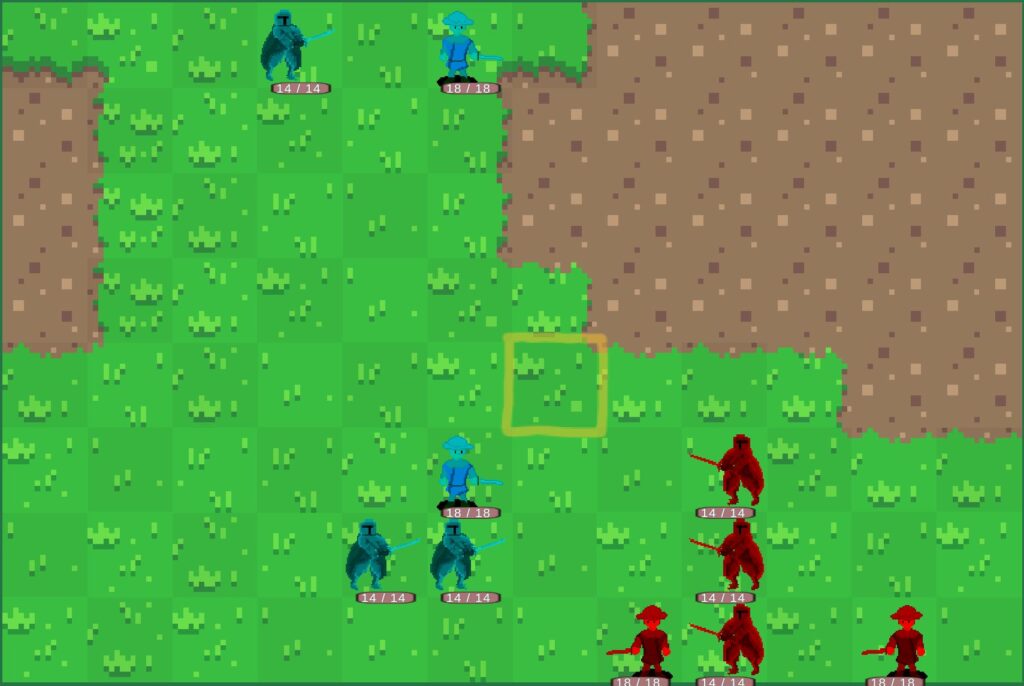

Example of the AI initiating an advantageous choice of combat in our final build

AI picking movement options in our final build.